Anton Webern

6 Stücke op. 6

Short instrumentation: 2 2 3 2 - 4 4 4 1 - timp, perc(5), hp, cel, str

Duration: 10'

Dedication: Arnold Schönberg meinem Lehrer und Freunde in höchster Liebe MCMIX

Instrumentation details:

1st flute

2nd flute (+picc)

1st oboe

2nd oboe

1st clarinet in Bb

2nd clarinet in Bb

bass clarinet in Bb

1st bassoon

2nd bassoon

1st horn in F

2nd horn in F

3rd horn in F

4th horn in F

1st trumpet in Bb

2nd trumpet in Bb

3rd trumpet in Bb

4th trumpet in Bb

1st trombone

2nd trombone

3rd trombone

4th trombone

bass tuba

timpani

percussion(5)

harp

celesta

violin I

violin II

viola

violoncello

contrabass

Webern - 6 Stücke op. 6 for orchestra

Printed/Digital

Translation, reprints and more

Print-On-Demand

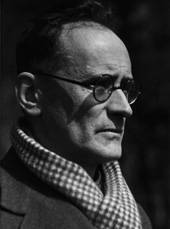

Anton Webern

Webern: Six Pieces for orchestra - op. 6Orchestration: for orchestra

Type: Taschenpartitur

Sample pages

Audio preview

Work introduction

When Webern wrote these pieces in 1909 he was in his mid-twenties; he had a university degree (Doctor of Philosophy) under his belt, was equally possessed by music and innocent, had acquired in Schönberg’s school the moral and technical equipment of a highly developed art of composition, and was scraping out a living as an assistant operetta conductor. His guiding examples, apart from Schönberg, were Mahler and Wagner and, probably without his being conscious then of their proximity, the erudite music-masters of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance who had occupied him during his studies at the Musicological Institute directed by Guido Adler at the University of Vienna.

The predecessors to Opus 6 were – besides several timorous student ventures, a piano quintet in C major and the imposing PassacagIia Op. 1 composed under Schönberg’s supervision – a few little vocal works (Op. 2, 3 and 4) and the Five Movements for String Quartet. The pieces for orchestra are the only larger, as it were symphonic, work into which Webern incorporated his “method”, that “method” he was later fond of associating with the concept “law”, in the double meaning of the Greek word “nomos”. Here, to be sure, the law is not yet identical to the row law of twelve-tone composition which subsequently raised his method to the state of musical autonomy, but it is already very much his own law. A different aspect of greatness. The rather conventional external display of instrumentation, which binds Opus 6 to the mental and emotional sphere of the Passacaglia and its silent partners, also counts, precisely because this Webernian law materializes spontaneously in the opposite direction, in concentration on internals, or more exactly, in the substratum of seeming insignificance that is brought to Iight. A world of musical micro-organisms is displayed.

The Six Pieces have an average length of 25 bars; the longest (IV) has 41, the shortest (III) has 11. The mental volume is of course incommensurable. There is nothing comparable in pre-Webern music, and as a category in the domain of occidental musical art it has remained present only through him.

For want of a better comparison, this musical short prose has often lumped together with the miniature or the aphorism. But it is as far removed from one genre as from the other, because it lacks both the jovial gesture of a pocket-sized art which aims at elegance, and the lofty nonchalance of a jigsaw-puzzle with thought splinters, elevated or profound as the case may be, often simply initiated, never seen through to a conclusion. The Six Pieces of 1909 and all the works that followed, even the shortest among them, are complex, closed forms, organized through and through and of the greatest formal stringency. Not piece-work and not an amorphous mixture in an unrestrained style of informal art. Their brevity is less the result of omission than of compression.

One of the most beautiful examples of the utter realization of a formal idea is found in the first of the Six Pieces: the delicate lineament of the melody parts. Distributed between clarinet, trumpet and harp, it slowly emerges from the tenuous, hovering sound-veil of the three introductory bars, shifts to the higher wind instruments (figure 2 / bar 7) and when these are joined by the strings is finely chiselled out by the latter (whereby at least two of the parts involved are led in counterpoint in a kind of stretto), finally sinking back into the sound-base at the end of the six-bar Coda. It has been shown in all its perfection. A characteristic detail of melody formation in later Webern is already noticeable here: the pattern introduced by the bassoon after figure 2 (bar 8), falling intervals of the fourth and fifth adding up to an augmented octave or minor ninth, their rhythmic modification in the lower strings and their melodic modification in the final bars of the trumpet part. Incidentally, the make-up of this piece and that of the last are strikingly similar, and it is scarcely an accident that both are in 2/4 metre throughout. The changing metres of the other pieces are in themselves an argument for that assumption.

The second and fourth pieces, with their restless crescendo drive to the extreme of a shrill fortissimo close, are out-and-out intensification forms. They stand in sharp contrast to the carefully balanced textures of the other movements. One sees (and hears) that the individual piece is not an isolated entity. It obeys a law of construction that makes it part of a superordinate totality. And the fourth piece, the longest, gives an inkling of the object of that totality. In it, Webern may finally have buried his hopes for better days than those bestowed by the old Empire, The fact that he later replaced the original marking, Marcia funebre, by a plain tempo indication, lessens not a bit the crushing force of this music.

The third and fifth pieces also have several traits in common, although the fifth is more than twice as long and would seem to be more closely related to the sixth piece by virtue of the longer rhythm of the melodic span, whereas the third piece contains reminiscences of the characteristic descending motive of the first movement in the third, fourth-last and antepenultimate bars. More distinctly than the other pieces, the third shows a feature that was later coined into a stylistic mark of the Viennese School: the tone-colour melody wandering through the entire orchestral spectrum. Schönberg had played it for the first time in his Fünf Orchesterstücke of 1908. His pupil may have drawn the idea for his own use additionally from the similarly conceived Hocket procedures of the late Middle Ages.

A comparison of the beginning and end of the 11-bar third piece shows by what simple means Webern often establishes, in even the most inconspicuous details, the cohesion that rounds off the whole: in this instance it is the quasi molecular movement of the rising and falling second in the viola and trumpet parts. The strength of cadence in the Six Pieces can best be estimated by taking into account the fact that it is exposed to stubborn opposition in the tension-field of totally emancipated dissonance, and that despite that opposition it is scarcely inferior to that of tonal cadences in effect.

It may be that the purely structural qualities of this music are hidden at times by the massive sound of a large orchestra, still filled with the pathos of the late Romantic era, and by the volatile gestures kindled by early Expressionism. The retouching done by Webern in 1928 toned down somewhat the contradiction between the external dimensions of the form and the bulk of the sound in which it is clothed, without altering, however, the stylistic cachet. The apparatus demanded by the second version of Opus 6, with its four horns, four trumpets, four trombones, its chimes, drums and other symphonic appurtenances, is still colossal in comparison to the forces involved in Webern’s later music. The plasticity of the sound, however, is considerably heightened by the virtual abandonment of part-doublings and ornamental accessories. Fullness gives way to values, pathos to contour. Exact knowledge of the work and its creator presupposes the knowledge of both versions.

The Six Pieces were performed for the first time in 1913, in the large hall of the Musikverein building in Vienna. The conductor was Arnold Schönberg.

F. S.