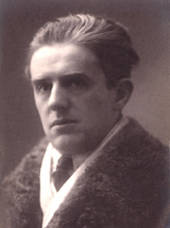

Gian Francesco Malipiero

*18 March 1882

†1 August 1973

Works by Gian Francesco Malipiero

Biography

Malipiero was born in Venice on 18 March 1882 into a family of musicians. Both his grandfather Francesco and his nephew Riccardo were composers, and his father, Luigi, was a pianist and conductor. From 1898 to 1899 Malipiero studied briefly at the Vienna Conservatory; from 1899 to 1902 he studied counterpoint with Marco Enrico Bossi at the Venice Liceo Musicale and was assistant to composer Antonio Smareglia; and in 1908 he attended Max Bruch's classes in Berlin.

Experiences which exerted a lasting influence on his creative personality were his encounter with early Italian music (Monteverdi, Frescobaldi, Merulo and others) and his stay in Paris in 1913, including his friendship with Alfredo Casella and his attendance of the première of Strawinsky's Rite of Spring which, as he later said, woke him "from a long and dangerous lethargy."

The First World War disrupted his life but, as he put it, "if I created something new in my art (formally and stylistically), it happened precisely in this period."

In the early 1920s in Rome, Malipiero joined Casella's Società Italiana di Musica Moderna, and together they founded the Corporazione delle Nuove Musiche.

From 1926 to 1942 Malipiero was active as editor of Monteverdi's complete works, and from 1939 until 1952 he was director of the Venice Liceo Musicale. As president of the Istituto Italiano Antonio Vivaldi he initiated the publication of the composer's instrumental music in 1947.

Malipiero's creative energy remained unbroken up to his death in Treviso on 1 August 1973.

About the music

Born in the same year as Igor Stravinsky, Malipiero shares with him the creative power to absorb elements of historic styles and compound them into a contemporary idiom.

In Malipiero's case, the artistic stance as well as the characteristic and individual approach to composition grow out of a much-reflected opposition to German and Italian traditions of the nineteenth century. In his view, the German symphonic concept of thematic unity runs counter to the Italian spirit. Hence he considers the musical tradition of Bellini, Donizetti and Verdi a dead-end; instead, his guiding figures are Claudio Monteverdi, Domenico Scarlatti, and Antonio Vivaldi.

However, Malipiero's personal integrity prevents him from mere stylistic imitation. He attempts to penetrate to the very essence of his given models, of which the most stimulating aspects are formal design based on free association rather than on abstract schemata, harmonic progressions that follow acoustic rather than theoretical necessities, and – on a more metaphysical level – the beauty of polyphonic textures and the discipline of language. These stimuli provide a basis for creative adaptation and transformation in which antiquity is mirrored in a modern spirit.

While Malipiero undoubtedly has strong links to the past, he has equally strong connections with his own generation's notions of the "present" and "new music." One of his preferred compositional techniques is the use of the fourth to build motives and harmony. From this starting point Malipiero proceeds to a remarkable augmentation of harmonic framework, passing from expanded tonality to bitonality, linearly conceived textures, and the primacy of melodic line over orchestral color. Harmony and articulation are employed with emotional restraint, and instrumental color is almost never used for its own sake. Malipiero abandons the the nineteenth-century inclination toward blending orchestral color in favor of Baroque principles of contrasting registers. In his works dating from the twenties, both timbre and harmonic detail occasionally recall Stravinsky.

While Malipiero's early works still manifest strong evidence of Debussy's influence, in the first volume of his Pause del silenzio (1917) his harmonies move unmistakably in the direction of atonality; and although after the First World War Malipiero briefly approaches expressionism – on a philosophical as well as musical level – later, in the twenties, his sense of harmony is characterized by a mainly diatonic, linear music ideal in which mediation between horizontal and vertical is increasingly perceptible. With this tendency, the degree of harmonic tension is lessened which, in turn, reveals Malipiero's link to tradition, evoking the spirit of Monteverdi and Vivaldi; harmony and melody show the influence of church modes: the result is true classicism of tone, form, and expression.

In the mid-fifties Malipiero's compositions manifest a complexity of texture, in which polyrhythms – resulting from linear and polyphonic stratification – play a more prominent role, also exerting influence on harmony. Works from this period give evidence of spiritual openness rare in his earlier works. Malipiero, at this stage, had obviously assimilated impulses from the Second Viennese School and its followers.

Unconditional sincerity, discerning cultivation, a noble attitude: these are the principle characteristics of Malipiero's music, often making use of extra-musical ideas (albeit in a thoroughly non-illustrative way). Nobility and sensitivity – though hidden behind apparent aloofness and reserve – form over a period of decades the basis of an expressive language which only seldom (in his earlier works) gives way to rustic vitality. More frequently to be found in his works are a pure spirit of music-making, an austere modern archaism, and a deep, inutterable sorrow.

Malipiero's goal of giving a new direction to Italian music by fusing the traditions of Gregorian chant, Renaissance, and Baroque music with the expressive means of contemporary musical thought seems outdated in the eyes of a younger generation following a completely different path. This fact, however, does not minimize the importance of Malipiero's œuvre which at its heights gives eloquent testimony of a synthesis between traditional and contemporary practices, constructive thinking and disciplined generosity, organized logic and personal originality.