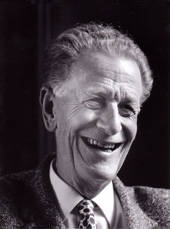

Frank Martin

Die Weise von Liebe und Tod des Cornets Christoph Rilke

Short instrumentation: 2 1 1 1 - 2 1 1 0 - alto sax(Eb) - timp, perc(2) - hp, cel, pno - str

Duration: 58'

Text von: Rainer Maria Rilke

Dedication: für Elisabeth Gehri geschrieben und Paul Sacher gewidmet

Solos:

Alt

Instrumentation details:

1. flute

2. flute (+ picc.)

oboe (+ c.a.)

clarinet in B

alto saxophone in Eb

bassoon

1. horn in F

2. horn in F

trumpet in C

trombone

perc (2): glockenspiel, timpani, hangig cymbal, cymbal a 2, smal military drum, 2 large basler drums, bass drum

celesta (played by perc)

harp

pno

violin I (8)

violin II (7)

viola (6)

violoncello (6)

contrabass (3)

Martin - Die Weise von Liebe und Tod des Cornets Christoph Rilke for alto and small orchestra

Printed/Digital

Translation, reprints and more

Frank Martin

Martin: Die Weise von Liebe und Tod des Cornets Christoph RilkeOrchestration: für Alt und kleines Orchester

Type: Partitur

Print-On-Demand

Frank Martin

Martin: Die Weise von Liebe und Tod des Cornets Christoph Rilke for alto and pianoOrchestration: for alto and piano

Type: Klavierauszug

Language: Deutsch

Sample pages

Audio preview

Work introduction

Millions of people died during the Second World War. Frank Martin, however, focused on the fate and death of one individual in Die Weise von Liebe und Tod des Cornets Christoph Rilke, which he composed in 1942–1943, based on a poem by Rainer Maria Rilke. His ballad-like music for alto and chamber orchestra is almost a monodrama (the piece has been staged several times) in which the soloist plays the role of narrator, observer and empathiser: a stirring challenge for any singer. The music responds immensely sensitively to each occurrence and each event in the tale, full of tension, impending doom and drama.

From the preface of the Repertoire Explorer Miniature Score:

Having finished Le Vin herbé for twelve solo voices, seven strings and piano, and having just completed his Cantate pour le 1er août, an occasional piece for chorus and organ or piano, Martin embarked on one of his major creations, Die Weise von Liebe und Tod des Cornets Christoph Rilke. Its genesis is recounted in his posthumously published memoirs A propos de ...: Commentaires de Frank Martin sur ses oeuvres (edited by Maria Martin in 1984): “In 1942 I was looking for a text to serve as the basis for a song cycle with piano accompaniment when my wife [Maria] drew my attention to Rilke’s exquisite prose-poem Die Weise von Liebe und Tod des Cornets Christoph Rilke. This work is hardly known among French-speaking readers; it is virtually untranslatable, and the translations one finds in bookshops even go so far as to disfigure it. I was excited by Rilke’s novella – so powerful, and yet so concise and tender – from my very first reading. Yet initially I rejected it as being inconsistent with my intentions: a suite of more than twenty songs – wasn’t that a bit much? Besides, Rilke’s novella, though divided into short scenes, has an epic plot; it depicts interlocking events rather than the unfolding of an emotion, which I considered to be the essential literary prerequisite for a song cycle. Finally I was afraid to set a text in a language not my own, as it has always been my precept in any vocal piece to reproduce the exact form and expression of the words. But the urgency and the magic of Rilke’s book shattered my resistance. My encounter at that time with Elisabeth Gehri, and the possibility of gaining her as a performer, convinced me to abandon my song cycle and to undertake a more extensive project. My decision was ultimately brought about by Paul Sacher’s words of encouragement [Sacher transformed Martin’s plan into a commission for his Basle Chamber Orchestra], which lent my project its definitive form. Through Sacher, the tenderness and translucency of a chamber orchestra could now pose as a counterfoil to the alto voice. Nothing could have better suited the text – this epic poetry with its infinitely concise and sensitive delivery, where everything, even the brutal scenes of war, is depicted in delicate hues. The small orchestra could do justice to this mood without running the risk of stifling it through the sheer number of musicians. As for the form, the division into scenes that I had undertaken in Le Vin herbé – without altering Bédier’s text – was already given in Rilke’s work, where it was accomplished more clearly and more decisively by the poet himself. The problem of the German language was solved by my close collaboration with my wife, for whom German is a second mother-tongue. We often discussed it; and together we defined the emphasis, duration and relative pitch of the various syllables in the text as well as the ever-refined, often difficult and fugitive gradations of expression that constitute the magic of Rilke. All that I can say about the music is that, for each scene, I tried to find a musical form that matched the literary form as closely as possible while preserving the character of each and every fragment, whether a simple narrative, a description, a lyrical outburst or a deepening of innermost emotions. […] To have spent a year living in the company of this text, probing it word by word, feeling all its refinements and emotional depths – nay, to have experienced it anew time and time again: all this means more to me than my recollections of spellbinding labour and intellectual enjoyment. It is as if Rilke’s words had become part of my life. It is my most earnest desire that a few people will find in my music something of what Rilke’s work gave to me.”

Elsewhere Martin describes how he noticed that the new work “ineluctably cried out for an orchestral accompaniment. To me, the material seemed to preclude the use of a chorus, and thus I remained true to my initial idea, which was to write the entire piece for solo voice. I wanted to lend perfect unity to the interpretation and to give Rilke’s work the character of a narrative, of a chanson de geste declaimed by a troubadour. This allowed me to avoid the theatrical impression that inevitably arises when several voices alternate in conversation. Rilke’s short epic poem consists of some twenty cantos, each with its own colour and special rhythm. It retains an incredible sensitivity even when depicting the brutalities of war. This sensitivity is so ethereal that I often asked myself whether music is capable at all of following all the nuances of Rilke’s thoughts and his delicate lines of expression. I did my utmost to adhere to the poem and constantly tried to attain a musical form that would be a portrait of the literary form.”

In 1943, after finishing the Cornet, Martin wrote the music to a ballet, Ein Totentanz zu Basel im Jahre 1943 [A Dance Macabre in the year 1943], which was heard for the first time during the performances on Basle’s Münsterplatz from 27 May to 10 June 1943. Encouraged by his work on the Cornet, he then set out on another project in German, the 6 Monologe aus Jedermann [Six Monologues from Everyman] after Hofmannsthal. The new work received its premiere in Gstaad on 6 August 1944, when it was sung by its dedicatee, the baritone Max Christmann, with the composer at the piano. (Martin’s popular orchestral version of the Monologues was added in 1949.)

Owing to the onset of a serious illness, Elisabeth Gehri, for whom Martin had originally conceived the Cornet and who was so emotionally attached to its music, was never able to sing the work in public. The première, given in Basle on 14 May 1945, was taken by the alto Elsa Cavelti and the Basle Chamber Orchestra, conducted by Paul Sacher. Many other successful performances of this extraordinary piece followed in rapid succession.

For the Repertoire Explorer Miniature Score please contact Musikproduktion Jürgen Höflich.